The Battle of Okinawa was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War in WWII and the bloodiest.

Called Okinawa Shima, the island was strategic to the U.S. war effort since it sported two airfields and was only 325 miles south of the Japanese home island of Kyushu. At that range, even medium range bombers could hit the home islands and cut off supply lines to the resource-hungry Empire. It was to be the staging area for the expected invasion of mainland Japan

It was a big island comparatively, sixty miles long and eight miles wide.

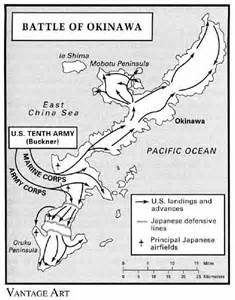

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Central Pacific Island hopping drive and General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific thrust converged on the torn rag shaped island.

In late March 1945, 1457 Allied vessels ferrying 182112 Army GIs and Marines assembled off Okinawa. Four divisions of the U.S. 10th Army (7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th) and two divisions of Marines (1stand 6th) prepared to hit the beach. The 2nd Marines was held in reserve.

Every man would be needed. Lt. General Mitsuru Ushijima’s 32nd Army, 110,000 strong, patiently waited in hidden bunkers and fortified ridges for the Americans to land. His strategy was similar to Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi on Iwo Jima. That is, avoid massive banzai charges and a stop-them-in-the-water tactics. Instead, lure the attackers ashore unmolested, and just when they think it’s going to be a walk-through, hit them with kou no kaze (“steel wind”) where they cannot receive naval and air support.

The General knew the war was lost, but he wanted to give the home islands time to prepare for eventual invasion, so he intended to inflict as many casualties on the enemy as possible. Simultaneously, an all out kamikaze attack on the fleet would bring the fighting directly to the Navy’s door and cut off the supply chain to the GIs and Marines.

On Easter Sunday, April 1st, the Americans stormed ashore. They hit the island simultaneously from the west side at a narrow point just north of the capital city of Naha (see map). They expected fierce fighting and were surprised when they encountered no opposition. By day’s end 75,000 troops had established a beachhead nine miles wide and three miles deep.

Once a beachhead was established, the plan was for the GIs of the 96th and 7thto wheel south and the two Marine divisions head north. The greatest April Fool’s joke was about to be played.

A ridge that rises to 1500 feet in the wild, mountainous north bisects the island. The southern portion contains most of the civilian population. It was there General Ushijima massed most of his forces.

The Japanese considered Okinawa part of their home islands and had a presence on the island for years. Most of their forces were located in the southern third of the island. Of central importance to defense of the island were three east-west ridges crossing the southern part if the island. These ridges formed natural defensive barriers to the American forces. Every gully, every ravine, every crossroads was triangulated by artillery, mortar and machine gun fire.

As the Army units moved south, artillery and mortars they couldn’t see hammered them. The guns were located in an elaborate network of cave connected by tunnels. An artillery piece would be rolled out on railroad tracks, bang away, and when the GIs thought they knew where the shelling was coming from, it would back into the cave out of sight. Mortar and machine gun fire came from heavily camouflaged positions. American artillery combined with naval guns inundated the Japanese positions, but they were mostly ineffectual. Casualties began to mount.

Meanwhile, in the north, the Marines were having only slightly better luck. Less heavily defended than in the south, the entrenched Japanese nevertheless battled furiously for every foot of advance by the attackers.

The fight degenerated into a dirty, gritty, primal, sometimes hand-to-hand combat, from cave to cave, pillbox to pillbox while staving off fierce counter attacks. Ammo and supplies began to run low. When they had run out of grenades or bullets, Marines and GIs would crawl to the bodies of their dead to retrieve whatever ammo they could find.

The incessant shelling from both sides, combined with torrential rains that commenced in May, turned the terrain into muck, sucking at boots, stalling even four-wheel drive vehicles. The constant rain disguised the Japanese positions even more. Bodies of fallen Marines and GIs had to be left where they lay, since retrieving them only exposed more men to Japanese guns. Decaying forms of Japanese, Marines and GIs, teeming with maggots slowly rotted in the muck. Every crater was half full of water and many held a dead Marine or soldier. They lay where they had been killed, still clutching their weapons. Swarms of flies crawled over their bodies.

For almost three months, Army and Marines bravely fought the tenacious Japanese. When the last shot had been fired, more men had fallen than at any other Pacific battleground. It was the greatest air-naval-land battle in history.

More than 100,000 Japanese died. A large number of civilians, perhaps as many as 25,000, also perished. It’s estimated tens of thousands were wounded. The U.S. Army suffered 4,600 KIA and 18,000 wounded. The Marines lost 3200 KIA and 13,700 wounded. The Navy, who fought off attack after attack of kamikazes, lost 5,000 KIA and 4,900 wounded.

The large toll of casualties shocked military strategists back in Washington. What would happen when American forces stepped on Japanese home soil? General MacArthur estimated that U.S. forces would suffer about one million casualties in an assault on the home island.

Ironically, the horrendous price the GIs and Marines paid for Okinawa swept aside opposition in high government and military levels for the use of the atomic bomb to end the war. Okinawa was the last land battle in the Pacific theatre.