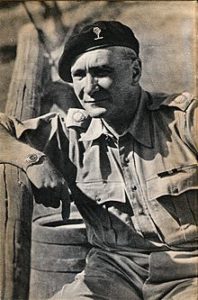

Isoroku Yamamoto

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was exhausted. A four-hour meeting with Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and the other militarists had left him drained. He slowly made his way from the Imperial Palace to his car. His driver, Ittoheiso (1st class petty officer) Takamasa Ikeda, noticed the admiral’s measured step. This would not be the time to engage him in their favorite subject, politics.“Good evening sir!” He saluted, bowed and opened the rear door of the big black sedan. Yamamoto slid slowly into the back seat and closed his eyes. “How did the meeting go, Admiral?

The driver’s informality with the admiral was normal behavior. Yamamoto wanted intelligent, engaged men around him. He didn’t stand on ceremony with most of them and he particularly enjoyed Ikeda’s company. He sighed, “Like most of them these days, Ikeda. Lots of talk, talk, talk. If we could harness their hot air, we wouldn’t have an oil shortage.”

Ikeda said solicitously, “There’s Macallan in the cabinet, sir.”

“Thank God.”

The admiral opened a small cabinet affixed to the back of the passenger side front seat. Inside was a bottle of his favorite scotch and two tumblers. He had developed a taste for the whiskey during his two postings in U.S. as naval attaché. Most Americans diluted their scotch with soda or water over a glassful of ice. Curtis Wilbur, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy, advised, “Isoroku, a true scotch drinker doesn’t dilute ‘the water of life’ with anything.”

He took Wilbur’s advice to heart. He poured himself a generous portion. Every time he drank scotch he thought of Wilbur. A thoughtful, kind and immensely intelligent man, he became a friend and advisor to the young attaché. The secretary had invited him to join his weekly poker game with his other friends in the government. It saddened him that his country might be on a collision course with his mentor’s.

As a naval major (equivalent to a Lt. Colonel) new to the Washington political world, he found the Americans an open, friendly people who, after a short time, welcomed him into their midst. “They couldn’t be more different than we are,” he thought. “They are forthright and have no hesitation when it comes to challenging authority. They don’t want war with anyone. Since their Great Depression, they have built a mighty industrial machine. We must not provoke them. If only I could get The Emperor and Tojo to understand that.”

Tojo had taken him aside during a break in the meeting. Admonishing the Admiral, he said, “My dear Yamamoto, you must get this approach to peace out of your system. The Emperor has begun to notice. There is a New Order in Asia and Japan will lead that Order. The European imperialists have helped themselves to many of our neighbors: the French in Indochina (Vietnam), the Dutch in the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia) and the British in parts of China. Japan is hemmed in and risks losing these important sources of raw materials. We must insure these sources of supply. That is why we went into China. China is our best market for exports and Manchukuo (Manchuria) provides natural resources that are vital.

“Japan is tired of these Europeans calling the tune in Asia. I intend to kick them out!” His voice got higher and higher as he spoke. “Japan will be an imperial power, I assure you! We will build it into an itto koku (first rate nation). Tojo laughed. “You will be an admiral in the most powerful navy on the high seas! But, my dear admiral, you need to get on board.” He laughed heartily at his pun.

“General, you make many good points and I agree with most of them. I simply believe it is important to include in these deliberations a posture of good relations with the United States.”

“My present attitude is not to initiate hostilities with the U.S. unless provoked. But they have provoked us! They are helping those corrupt Kuomintang (Nationalist Chinese government) monkeys against us! They have initiated an oil embargo and frozen all Japanese assets in the U.S. Intolerable!

“General, I’m aware of that, but….

Tojo interrupted, his face a mask of stone. “Yamamoto, you need to understand that poor negotiations by our leaders in the past have put The Empire in a poor bargaining position. Foreigners living here are not subject to our laws. Inconceivable! And I find their racial prejudice insulting!

“General, I share your revulsion with these coercive acts. With you as Prime Minister, I’m sure Japan will do better at the bargaining table. I only suggest that when it comes to the United States, we tread carefully. I lived there for several years and traveled the country extensively. It is a huge country! Three thousand miles from one end to the other. Enormous industrial capacity. A population that is five times ours. We cannot win a fight with them. They could bury us.”

Tojo eyed Yamamoto carefully. The admiral had risen rapidly in the ranks, had friends in high places and was extremely competent. No point in making him an enemy. But he warranted watching.

“I will take your remarks into consideration, Admiral.”

The telephone rang in Yamamoto’s office. Chief of Staff Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki picked up the receiver. “Ah, Ugaki. I hope you are well. This is Mitsumasa Yonai.”

“Minister Yonai, it is good to hear your voice.” Their informality harked back to years as classmates in the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy. Yonai had been first in his class, two years ahead of Ugaki. He had only recently been appointed Minister of the Navy.

“May I speak to the Admiral?”

“I’m quite sure he would welcome your call, minister.” Holding the receiver, he buzzed Yamamoto’s office. “Minister Yonai on the line for you, sir.”

“This is Yamamoto, Minister Yonai.”

“Ahh, Yamamoto. Are you well?”

“Quite well, thank you, Minister.”

“Very good. The reason for my call is to advise you are being assigned to the Combined Fleet as Commander-in-Chief. You will, of course, be promoted to Naval General (four star admiral). Your appointment is effective immediately.”

“Thank you, Mr. Minister. I was getting tired of sailing a desk.”

After Yonai hung up, Yamamoto called for his Chief of Staff. “Ugaki, break out the scotch, we’re going to sea! At last!”

“If it’s all the same to you, sir, I’ll have a taste of sake. Congratulations.” The men raised their glasses and toasted each other.

It was a blustery, overcast day. An iron gray sea slapped sluggishly against the massive hull of the Admiral’s flagship, the 70-ton battleship Yamato. Yamamoto and Ugaki disembarked the ferrying launch which had brought them from the naval base pier. As they boarded the large battleship, the boatswain piped them aboard with a “VIP Coming Aboard” whistle. Waiting to greet them was the Captain of the Yamato, Minoru Genda.

Greeting the new Commander-in-Chief with a sharp salute, a smile and a deep bow, Genda said, “Welcome aboard, Admiral.” For the captain of the ship to personally greet a guest arriving on board demonstrated the highest regard and respect for the guest. Ordinarily, the officer of the deck greeted any newcomers and escorted them to the captain’s office.

“Good to see you again, Genda. And congratulations on your appointment to Captain of the Yamato. It is a noble ship and I know you will sail her well. May I introduce my Chief of Staff, Admiral Matome Ugaki?”

Genda and Ugaki exchanged salutes and bows. “Welcome Admiral Ugaki. Let me get you gentlemen out of this weather and into a glass of the Macallen.”

Yamamoto chuckled. “You are the ever resourceful sailor, Genda. However, Admiral Ugaki is traditional. He prefers sake.”

“I believe I can accommodate the Admiral. I have a goodly supply of Junmai sake on hand. If you gentlemen will follow me.”

After Yamamoto and Ugaki had comfortably settled into the plush chairs in the captain’s stateroom and had their glasses charged, Genda opened the conversation. “Admiral, you have been abreast of recent developments emanating from the Prime Minister’s office. Could you bring me up to date? Rumors are flying like seagulls around the Fleet.”

“My dear Genda, this conversation never took place. A reality is, seagulls will probably continue to fly. Another reality is that the Army is dragging the Navy into expanding the war. The militarists are even talking about attacking the United States. There is a very strong likelihood that will happen in the very near future. Still another reality is that one of the reasons I’m here is that I’m unintentionally under a political cloud. Important people would be quite happy to see me dead. Going to sea may save my life. Ironically, I’m delighted to be standing on the deck of one of the Emperor’s ships.” Yamamoto smiled. “By the way, Genda, given my circumstances, serving with me may not help your career. I’ll transfer you to another ship if you wish.”

“I wouldn’t consider it, sir.”

“Thank you, Genda.”

The Yamato was undergoing combat trials in the western Pacific off the southern island of Shikoku. There was a knock on Yamamoto’s stateroom door. “Sir, we have received a radio message. ‘For your eyes only.”

“Thank you, lieutenant.”

“Thank you, lieutenant.”

When the lieutenant had left, Yamamoto opened the decrypted message.

Draft plans for naval support for an attack on the Philippine Islands. Need completion of same within thirty days.

“Well, this is it,” he thought. “Only they’re going after the wrong islands. Our left flank is vulnerable as long as the U.S. Pacific Fleet is in Hawaii.”

The tension in the office of Naval Minister Mitsumasa Yonai’s office could be cut with a samurai sword. Prime Minister Hideki Tojo stood before the assembly and announced, “Negotiations with the U.S. regarding sanctions and our presence in China are going nowhere. It is essential for Japan’s security that we establish ourselves in those countries that are currently providing the raw materials for our survival. Consequently, the Emperor has approved military operations for our presence in strategic areas of Southeast Asia, effective immediately.”

The tension was accompanied by silence. Yamamoto thought, “Well, there’s no turning back now. God help Japan. If America mobilizes, we are doomed.”

Tojo continued. “General Masaharu Homma’s 14th Army is poised to strike the northern most island of Luzon in the Philippines as we speak. We must support his invasion by eliminating any naval threat in that area, particularly the British.”

When it was Yamamoto’s turn, he said, “Gentlemen, if we are to expand the war to the south, I believe it is imperative to secure our left flank. The U.S. Pacific Fleet moored at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii is a dagger to our throat. There are significant U.S. Army installations in our path of advance, particularly in the Philippines. When we capture those islands, we’ll have to intern a large U.S. force. The U.S. will be forced to react. Their fleet is larger than ours and poses a significant threat to any large-scale military thrust southward. I propose we destroy the American fleet before any ground assault takes place.”

Yonai said, “How do you propose to do that, Admiral?”

“I have consolidated the carrier forces into a unified strike force called The First Air Fleet. It gathers our six largest carriers and their support vessels into one unit. I am in the early stages of drafting a plan that would involve sailing that fleet within a couple of hundred miles or so of the islands of Hawaii. I will unleash a large group of dive-bombers and torpedo bombers, which will be supported by fighters on the unsuspecting American ships. It will cripple the U.S. Navy for an extended period and give us time to complete our dominance in Asia.”

The Naval General Staff sat in stunned silence. It was audacious, risky and daring. But these were men who had, all of the professional lives, taken minimal chances on virtually everything. In their view, the risk was too great.

Admiral Osami Nagano, chairman of the General Staff, exclaimed, “My God, Yamamoto, what are you proposing? You could lose the fleet!” There were murmurs of approval to his remarks around the table.

“Gentlemen, I realize it is a dangerous undertaking, but the odds are too good not to take. If we fail, we’d better give up the war.”

Tojo kept his silence. He looked at Yamamoto through slitted eyes with the slightest hint of a smile. “I finally have the Admiral where I want him. He will fail and I will have no opposition.”

There was much opposition to the plan from the naval officers. Arguments and comments flew back and forth. Finally, Nagano spoke. “I’m sorry, Admiral, it’s out of the question. It’s insane to take such a risk.”

Yamamoto, ever the clever poker player, deceided to raise the stakes. “Well, gentlemen, I believe it is a risk worth taking. When you overrun those U.S. Army installations and begin putting their men into POW camps, the American Fleet, loaded to the gunwales with Marines, will descend on us like angry bees. We will be forced out of Manchukuo and China and will lose all we have gained.”

Tojo had a card to play. “My dear Admiral, you overestimate the Americans. Their government has gone on record as being isolationist. Their navy can be easily dealt with by ours.”

Yamamoto saw Tojo’s game. Now it was time to call and raise again. His hole cards were his enormous popularity within the fleet and his connections with the royal family. He said, “If my plan is rejected, I will be forced to tender my resignation.”

He had stunned them again. Tojo looked troubled. He hadn’t counted on Yamamoto’s tolerance for risk. He thought, “If he does resign, he will be finished. He’ll be in charge of folding blankets at the Yokosuka Naval Base for rest of his career.”

“Good day, gentlemen.” Yamamoto stood, bowed deeply and walked out of the room.

The answer wasn’t long in coming. He was poring over paperwork in his office on the Yamato. The communications officer knocked on his door.

“Come.”

“Sir, a ‘for your eyes only’ for you.”

“Thank you, lieutenant.”

Proceed with assault plans on U.S. Pacific Fleet. Advise when you are prepared.

Yamamoto allowed himself a smile. “Ugaki!” His chief of staff appeared almost immediately from adjoining quarters. “I just went eyeball-to-eyeball with the General Staff and they blinked. Let’s have a toast to a successful mission.”

Ugaki smiled. He knew his boss liked nothing better than to be under way at sea. “Congratulations, sir. Now we can really get to work. Shall I arrange a meeting with our senior officers?”

“Absolutely. At this point, I need to meet with the carrier commanders and the commander of the air arm. Tell them I would like to meet them here tomorrow at 14:00.”

The next day the captains of the carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryo, Hiryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku and the two senior commanders of the air fleet made themselves as comfortable as possible in Yamamoto’s small stateroom. Admiral Ugaki took one of the small chairs in a corner.

“Gentlemen, good afternoon. What I’m about to say cannot leave this room. I have given the responsibility of inflicting a crippling blow on the U.S. Pacific Fleet on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. This is their headquarters. Their moorings surround the small island called Ford. They are compacted there in a small area and present an excellent target.”

“It is my belief that we must inflict such a powerful strike on their fleet that they would not be able to threaten us for six months to a year. We cannot expand the war to other areas until we secure our flank. If we fail in this mission, we will have lost the war and all we’ve gained thus far.”

“The air assault will be comprised of a fleet of about 350 aircraft, consisting of dive bombers, torpedo bombers and fighters. Preparations for this mission begin immediately and supersede anything you are working on presently.” Turning to Ugaki, he said, “Admiral, would you show our guests what we have so far.”

Ugaki spread a large map on the stateroom table. He said, “Gentlemen, this is a map of the Ford Island mooring of the U.S. Fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. As you can see, the Americans have moored most of their larger ships side by side. These are our primary targets. We will launch our aircraft in two waves, approximately thirty minutes apart. The first wave, under the able command of Commander Fuchida, will be the primary attack force. The second wave, under the most excellent Commander Shimazaki will attack targets of opportunity and anything that the first wave misses. Our planes will be divided evenly among the six carriers.”

The officers looked at each other. Some took deep breaths and exhaled. Others pursed their lips and looked intently at the deck.

The Captain of the Akagi, Kiichi Hasegawa, asked, “How much preparation time do we have?”

Ugaki said, “We have extensive training and target analysis ahead of us. I would expect we will be ready to sail in five months. Further details will be sent to you shortly, to which you are welcome to add your comments. For obvious security reasons they will be distributed to you by courier under a ‘for your eyes only’ basis. There will be no radio contact regarding the mission.”

Yamamoto stood. “Gentlemen, thank you for attending. Admiral Ugaki and I will contact you with further details.” The officers and their hosts exchanged salutes, deep bows and filed silently out of the room.

The next months were a whirlwind of activity for Yamamoto and his men. Detailed mock-ups of the harbor and the positions of the ships moored there were studied by all pilots. They were assigned specific targets to attack when they arrived. The pilots had to learn how to launch torpedos in shallow water since the harbor around Ford Island was only 45 feet deep. Specially crafted bombs for the dive-bombers were constructed by machining down their nose to make them armor-piercing. Exercises at sea were performed regularly. Yamamoto supervised all training and exercises personally. After four months had elapsed, he told Ugaki, “I think we’re ready.”

As if to signal a good omen to Yamamoto’s efforts, November 26th, 1941 dawned bright and cheerful. The task force comprised of the six carriers, their flight decks swollen with attack aircraft, set sail on an easterly heading. Sailing protectively around the carrier force were two battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, eight tankers and twenty-three submarines. Radio silence was strictly maintained. All communication with surface vessels would be by flag or by a signal projector utilizing Morse code.

Avoiding shipping lanes and zigzagging to avoid U.S. submarines, the task force arrived at the launch point, 275 miles north of Pearl Harbor early on December 7th. The pilots were given their last instructions. Primary targets for the torpedo planes were the highest value targets, battleships and carriers. Fighters were to strafe as many parked aircraft as possible. Dive-bombers were to hit ground targets of opportunity.

As the fleet turned into the wind to accommodate the aircraft launch, Commander Fuchida, in the lead plane, signaled all first wave pilots, “Follow me!” The crews of the carriers stood on the flight deck, waved their caps in salute, threw their arms into the air and yelled, “Banzai, Banzai, Banzai!” The slower torpedo planes led the attack, relying on the element of surprise. The dive bombers followed. In all, 183 planes in the first wave took off on a southerly heading.

In an hour Pearl Harbor hove into view. Fuchida couldn’t believe his luck. Ford Island was packed with warships. He signaled the task force, “Tora, Tora, Tora! (Tiger), advising that the attack had caught the fleet at their moorings. It was also the signal for Commander Shimazaki’s second wave to join in.

In two hours, the attack was over. Four battleships were sunk including the Arizona and West Virginia; three others severely damaged; three cruisers damaged; three destroyers and three other ships destroyed. 188 American aircraft were destroyed. The American fleet suffered over 2400 killed in action (KIA) and over 1200 wounded. Civilian casualties were 57 KIA, 35 wounded. Japanese losses were only 29 aircraft and 64 KIA.

It was a massive body blow to the U.S. Navy, but not a knockout punch. All of the U.S. carrier force were at sea on various assignments and suffered no losses. This would come back to haunt the Japanese Navy in the future. The very ships they missed at Pearl would ultimately help cause Japan’s defeat. Naval warfare was shifting from battleships to carriers. The U.S. recognized this. The Japanese did not.

It was a massive body blow to the U.S. Navy, but not a knockout punch. All of the U.S. carrier force were at sea on various assignments and suffered no losses. This would come back to haunt the Japanese Navy in the future. The very ships they missed at Pearl would ultimately help cause Japan’s defeat. Naval warfare was shifting from battleships to carriers. The U.S. recognized this. The Japanese did not.

Admiral (4 stars) Husband Kimmel, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, was relieved and demoted to Real Admiral (2 stars). He retired shortly thereafter.

Militarily, it was a great victory for Japan. On a political level, it was a disaster. It aroused in an isolationist-leaning America a passion for revenge. It was a “sneak attack,” and a “stab in the back.”

Advised of the victory, Yamamoto confided to his Chief of Staff Ugaki, “I fear all we have done today is to awaken a great sleeping giant.”

The following six months saw the Admiral delivered one victory after another. The Japanese were ecstatic. Here is our Admiral Horatio Nelson (British Naval hero in the Napoleonic Wars), they thought.

The tables began to turn at the subsequent Battles of Midway Island and Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy had broken the Japanese secret code by which they communicated confidential messages among their forces. By reading deciphered messages from the Japanese Fleet to and from Imperial Navy HQ, the Navy knew the positions of Yamamoto’s attack force. The U.S. carriers, untouched at Pearl Harbor, dealt Yamamoto severe losses.

He continued to fight on, but pessimism sank in. He wrote to a friend in August of 1942, “I sense that my life must be completed in the next 100 days.”

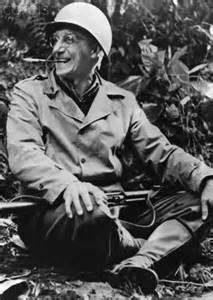

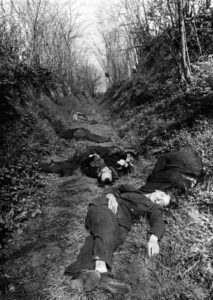

He was close to correct. On April 18th, 1943, resplendent in his class A white dress uniform, he boarded a Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber for an inspection tour of Japanese bases. Meanwhile, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, had received intel that disclosed Yamamoto’s itinerary. Nimitz immediately scrambled a squadron of Army P-38 fighters. They intercepted Yamamoto’s plane and shot it down over the Japanese-held island of Bougainville. There were no survivors.

Japan was stunned. They had lost their greatest wartime naval strategist. They had lost their Horatio Nelson.

His remains were recovered and sent to Japan. Honors poured in from Emperor Hirohito and other Axis powers. Hirohito awarded him the Grand Order of The Chrysanthemum. Hitler made him the only foreigner to receive the Knight’s Cross-with Swords.

His successor, Admiral Mineichi Koga said, “There was only one Yamamoto and no one can replace him.”