Dress Rehearsal for D-Day

“It was a disaster which lay hidden before the World for 40 years…an official U.S. Army cover-up.”

What would prompt such strong words from several news outlets including the BBC? The story goes back to the early morning hours April 28th, 1944.

Earlier that previous day, an assault force of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division had gone ashore at Slapton Sands, a beach in southern England. That location was chosen because it closely resembled a beach on the French coast of Normandy, code named “Utah.” The exercise was a dress rehearsal for The Big Show on June 6th.

Assault conditions were made as realistic as possible to accustom the troops to true combat conditions that they would face on D-Day, including live firing from naval guns and on-board artillery. Individual soldiers also had live ammunition in their weapons.

Assault conditions were made as realistic as possible to accustom the troops to true combat conditions that they would face on D-Day, including live firing from naval guns and on-board artillery. Individual soldiers also had live ammunition in their weapons.

Shortly after midnight, eight LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) arrived, ferrying combat engineers and quartermaster personnel. Accompanying them were heavy trucks, jeeps and heavy engineering equipment, which were to be off loaded shortly after the initial “assault.”

Nine German Schnellboots (torpedo boats, similar to U.S. PT boats), on routine patrol, picked up unusual heavy radio traffic emanating from the Slapton Sands area. Curious, they decided to investigate. They were amazed to see a small flotilla of what they thought were destroyers. The commander of the Schnellboot squadron ordered an immediate attack.

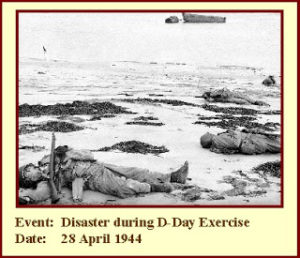

Germen torpedoes hit three of the LSTs. One had most of its stern blown off, but was able to limp into port and safety. Another exploded in huge fireball, fed by the large gasoline supply on board. The third keeled over and sank in six minutes.

There was no time to launch lifeboats. Trapped below decks, hundreds of sailors and soldiers went down with their ship. Others leapt into the sea, but soon drowned weighted down with waterlogged overcoats. Many men died of hypothermia in the chilly 60-degree water.

The toll of the dead and missing was 198 sailors and 551 soldiers. It was the costliest training disaster involving U.S. forces in WWII.

Not only were Allied commanders dismayed at the loss of life, but the loss of two LSTs meant there were none available as a reserve for D-Day. Additionally, they were concerned that one or more soldiers that may have been captured by the Germans who knew secrets about the coming invasion would be forced to “spill the beans.” There were about ten officers in the flotilla that were intimately involved in invasion planning and knew the assigned Normandy beach locations. A good night’s sleep was hard to come by for the brass until these men could be accounted for. It was soon learned that all of them had drowned.

An official investigation was launched. It was revealed there were two factors that may have contributed to the tragedy: Only one ship was available for flotilla escort duty, a British corvette, and an error in radio frequencies.

Due to typographical error, the LSTs were on a different radio frequency than British naval headquarters ashore. A British ship spotted the German torpedo boats and that information was transmitted to the corvette, but not the LSTs. The captain of the corvette assumed the information was transmitted to the LSTs so he made no effort to contact them.

Whether or not these factors would have had any measurable effect on the outcome is impossible to say.

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), for fear that the Germans would learn of the debacle, ordered a lockdown on any information until after D-Day. A press release was issued in July 1944 by SHEAF to Stars and Stripes newspaper describing the incident.

Ten years after D-Day, a monument was unveiled at Slapton Sands honoring the people of the area “who generously left their homes and their lands to provide a battle practice area for the successful assault in Normandy in June 1944.”

The incident was almost forgotten until 1968 when a policeman retired to the Slapton Sands area. He noticed the monument, but on walks on the beach, he began to find unexpended cartridges, fragments of uniforms and uniform buttons. He thought, “There’s a monument to the people here but not to the soldiers.” He learned from a fisherman that that a Sherman tank lay in the offshore waters. He smelled a cover-up. His story reached the news media and accusations of an official cover-up took off. The fact that the U.S. government didn’t erect a monument to the soldiers and sailors added to the rumors.

What was forgotten was the press release to the Stars and Stripes newspaper in 1944 fully describing the incident. It became the cover-up that wasn’t.

Thanks to Jerry F., Seattle, Washington for his input.