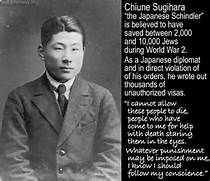

Hugh O’Flaherty

At six feet two inches tall, with a shock of hair that seemed to add two inches to his height and tipping the scales at 225 pounds, Hugh O’Flaherty looked more like a rugby flanker or a football linebacker than a priest entitled to be addressed with the honorific “Monsignor.”

But with a twinkle in his eye behind horn-rimmed glasses and a ready smile on a cherubic face, he put anyone at ease that may harbor apprehensions about his commanding presence.

Behind those twinkling eyes rested a razor sharp mind, intense spirituality, immense charity and strong moral courage.

A son of County Cork, in Southern Ireland, he always knew he wanted to become a priest. He attended Mungret College, a Jesuit college dedicated to preparing young men for missionary priesthood. He was active in sports and it was here he developed a life long passion for golf. He later told a friend that there was “nothing like golf for knocking all the troubles of this poor world out of your mind.” Upon graduation, he was posted to Rome for further study and ordination.

He became a Vatican diplomat, seeing service in Egypt, Haiti, Santo Domingo and Czechoslovakia. In 1934 he was appointed Monsignor and recalled to the Vatican’s Holy Office as a Scrittore, or Writer. His job was to examine the Church’s teachings and important doctrinal matters. He thoroughly enjoyed his new post. He developed a wide range of contacts among Roman society. Many of these were when he was a member of the Rome Golf Club. “[He] seems to know everyone in Rome,” a friend said sometime later.

SS-Oberstrumbannfuhrer (Lt. Colonel) Herbert Kappler was born into a middle-class family in Stuttgart in 1907. Upon graduation from high school, he attended a technical college studying electrical engineering. He found work in Stuttgart as an electrician.

He joined the Nazi Party in 1931. At the same time he became a stormtrooper in the Sturmabteilung (SA). A para-military wing of the Nazi Party, they were intensely anti-Semitic and popularly called “the brownshirts,” from the color of their uniforms. They provided security for Nazi Party gatherings and in their spare time, persecuted Jews and other “undesirables.”

The next year he left the SA and was accepted into the Schutzstaffel (SS), a para-military unit that had once been a part of the SA. With the demise of the SA in a purge led by Hitler, the SS took over many of their duties. Under the direction of Reichfuhrer Heinrich Himmler, it became Hitler’s “Praetorian Guard,” and was greatly expanded in scope and size.

Intensely ambitious, with a talent for secret police work, Kappler rose rapidly in the ranks of the SS. Fluent in Italian; he was promoted to SS Strumbannfuhrer (Major) and assigned as a liaison officer to the government of Il Duce, Benito Mussolini.

When the German military occupied The Eternal City, he was made Chief of Police and head of The Gestapo in Rome. He controlled the city from the former German Embassy. It was his office, a prison and an interrogation center. Number 20 Via Tasso was synonymous with torture and brutality. It was a final destination for many Jews, partisans, communists, gypsies and anyone harboring escaped Allied POWs.

A narrow, Teutonic face, piercing eyes, a three-inch dueling scar on his cheek and a suave half-scowl masked a relentless, ruthless servant of National Socialism.

On September 1, 1939, Hitler ripped into Poland and began the bloodiest conflict in human history, WWII. By 1941, war was raging across Europe. There were tens of thousands of Allied servicemen held in POW camps all across Italy.

Pope Pius XII, concerned about the welfare of these men, wanted routine checks made on the camps to insure they were being held in accordance with international conventions. He wanted two of his officials to make regular visits to the camps. He appointed Monsignor Borgoncini Duca as his Papal Nuncio (diplomatic representative). He needed an English speaker to assist Monsignor Duca as translator and act as secretary. He asked Monsignor O’Flaherty to perform the task.

It changed Hugh O’Flaherty’s life.

He had always thought of himself as a neutral observer. He had always felt the Allies and the Germans were equal opportunity propagandists. A son of Erin, he had seen the brutality brought to Ireland by the “Black and Tans” (Royal Irish Constabulary) after WWI and had grown up despising the British. He once said, “I don’t think there is anything to choose between Britain and Germany.”

But stunned by what he saw in the camps, he became increasingly aware that British or not, more needed to be done to alleviate the suffering of the war’s victims. He was not content to merely report on their condition. Through a friend at Vatican radio he began to pass on messages from prisoners so that their relatives would learn that they were alive and safe. The friend, a Fr. Owen Sneddon, added tidbits of information to the government-prepared scripts that were of vital importance to the POWs next of kin.

Over time, the Monsignor became the prisoners “champion.” He regularly lodged complaints about how the men were treated. He distributed thousands of books around the camps. He cut red tape to speed up distribution of Red Cross parcels and clothing.

To the Italian military, which had responsibility for the administration of the camps, he became an annoying gadfly. Political pressure was applied to the Vatican to remove him, claiming his “neutrality had been compromised.”

The true reason: the military wanted him out of the way because he was exposing the mistreatment of prisoners. In 1942, he was “relieved” and returned to his duties in the Vatican.

Under the Lateran Treaty of 1929, the Vatican was guaranteed independence from the Italian State. This agreement defined the 108-acre Vatican City as well as some 50 acres outside the City’s walls. The Holy See (ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Catholic Church) pledged to remain neutral in international conflicts and not interfere in Italian politics.

In late 1942, a British seaman, reaching the highest rung on the ladder of chutzpah, walked out of a POW camp, scrounged some workers clothing, stole a bicycle, calmly pedaled his way into St. Peter’s Square and slipped into the Vatican gardens. A sympathetic Vatican policeman delivered him to Sir D’Arcy Osborne, Britain’s Minister to the Vatican. Osborne lobbied the Vatican authorities to allow the seaman to stay. They agreed. He lived at Osborne’s apartment for a time, eventually being exchanged for an Italian prisoner.

The episode struck a chord with Osborne and his neighbor, O’Flaherty. This was to be first of a long line of escaped prisoners they would deal with. Unknown to the men at the time, the seaman would be the forerunner of hundreds of escapees who made their way directly to the Vatican.

Osborne and O’Flaherty, despite their differing backgrounds and outlook (Osborne was Protestant, upper class and related to British royalty), were friends and neighbors who had small apartments in the Santa Maria Hospice. They shared a passion for golf and dismay over what the war was doing to Europe. That friendship would be critical in what would become the Allied Escape Line.

O’Flaherty’s reputation as someone who could be of assistance to people in trouble with the fascist authorities spread. Initially, he saw his role as to simply make suggestions and offer advice. He referred inquiries to safe locations, usually convents and monasteries. He quickly began to be a rallying point for those in danger, particularly Jews and Anti-Fascists. As oppression grew, so did his activity. He began to hide people in his own residence. Three escaped New Zealand soldiers, remembering his kindness in the POW camps, showed up seeking sanctuary. He hid them in an empty room in the Vatican.

The Allies had landed in the south of Italy and were making a slow, painful slog north. As they did, Italian guards at more and more POW camps deserted. There were about 80000 Allied servicemen and civilians imprisoned in 72 camps throughout Italy. The desertion freed about 50000 of them. Most were recaptured, but some 18000 were not. The trickle of escapees became a river. The river flowed north to Rome and the Vatican. Three South African POWs hiked to Rome and remembering the Monsignor from a visit, showed up seeking help. He had them placed in a private accommodation. At the same time, he arraigned safe housing for two downed American pilots. He hid escapees in flats all over Rome, in farms, convents and monasteries. One of the hideouts was in a building next to Kappler’s headquarters.

The monsignor began to be overwhelmed. Clearly a more organized and secure approach was necessary. O’Flaherty approached his friend and golf partner, Sir D’Arcy, for help. After all, weren’t many of the escapees British? The British minister demurred. He said he was being closely watched and needed to be very careful not to compromise his position. He did, however, offer financial aid from his own pocket and the services of his butler, John May.

May was the epitome of the British manservant: Discreet, low-key, capable, a “fixer” with fluency in Italian with extensive contacts throughout the city. Described by O’Flaherty as “a genius, the most magnificent scrounger I have come across.”

May convinced the Monsignor that he needed more help managing the flood of people seeking help. “Oh, I know you have every ‘neutral’ Irish priest in Rome helping you…but excuse me, they’re only priests…they don’t know their way around like I do, and some of my, ahhh, ‘friends.”

As a result, the Council of Three was established, consisting of O’Flaherty, May and a Count Sarsfield Salazar of the Swiss legation. As a diplomat from a neutral country, the Count was an ideal ally since many of those arriving in Rome sought out the Swiss Legation. His role was to see to it that money, food and clothing reached escapees hiding out in the countryside.

It was during this period the Vatican came under intense scrutiny by Kappler and the Gestapo. He was convinced that a nest of foreign diplomats in the officially neutral Vatican were spying for their representative countries and he wanted them expelled.

Squads of Gestapo agents and Italian fascist police placed many of the diplomats under constant surveillance. Osborne and Harold Tittmann, the U.S. Charge d’Affaires, were of particular interest to Kappler. Their movements, phone conversations and mail were closely monitored. Due to his activities in the POW camps, his friendship with Osborne and his activities in aiding escapees, O’Flaherty was similarly in Kappler’s crosshairs.

Dossiers on the men began to fill. Who they met on the streets, their lunch partners, their visitors; the minutia of their daily life all found a home in their file at Gestapo headquarters.

The reason the men’s file became so large is that Kappler had a “mole.” Alexander Kurtna was a 28-year-old Estonian seminary dropout. He had secured work as a translator in a Vatican department that looked after priests based in Eastern Europe. Kurtna began to feed Kappler with confidential information about Vatican activities. He joined Kappler’s ever-expanding network of informants in The Vatican and The Eternal City.

One of Kappler’s contacts in the police advised him that there was an illegal radio transmitting within the city. It was traced to the home of Princess Nina Pallavicini, a member of one of Rome’s ancient families, a social acquaintance of O’Flaherty and an ardent anti-Fascist. A raiding party was sent out to investigate. The Princess narrowly escaped the intruders by jumping out of a rear window and running for her life to the Vatican. She asked to see the Monsignor. He took her in and gave her long-term sanctuary. She repaid his kindness by spending the remainder of the war making false documents for Allied escapees.

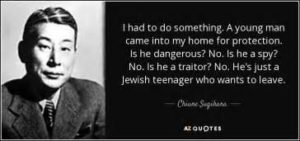

The war had now entered a dark, frightening stage. At the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, a systematic plan, “The Final Solution,” was instituted. Anti-Semitism was and had been rampant in Germany and Austria, but this was different. The plan’s goal was the complete emptying of Europe of Jews by genocide. Death camps were established in remote areas. Deportations of Jews, gypsies, gays and other “undesirables” to those camps became a daily routine all over Europe.

Kappler was entrusted with assembling Roman Jews for transport to death camps. Additionally, he was involved in suppression of resistance groups, rounding up “enemies of the state” for deportations to extermination camps.

Kappler privately opposed the plan, believing it tied up too much needed manpower and concerned it would make Rome more difficult to rule. When he voiced his reservations to his superiors in Berlin, he was brusquely told to follow orders. Not wanting to appear less than loyal to the Reich, he began purging Rome of its Jews.

In the early morning hours, SS men and Italian Fascist police were banging on Jewish doors with rifle butts. In most cases the houses were ransacked. The occupants were drug out on the streets, some still in their nightclothes. Children screamed and cried. Adults openly prayed. They were thrown into trucks, taken to a railway station and shoehorned into railway cars. Final destination: Auschwitz death camp.

The Jewish deportations infuriated O’Flaherty. “These gentle people are being treated like beasts!” Any vestiges of his neutrality evaporated by the sight of human beings jammed into railroad cars like so much cattle. He remarked to a colleague, “the sooner the Germans are defeated, the better.”

Ironically, the brutal treatment of the Jews helped O’Flaherty’s budding escape organization grow. Now ordinary Romans who had previously been indifferent to the Germans offered the Monsignor their help. The Augustine Maltese Fathers, the Brothers of Christian Schools and many of Rome’s society stepped forward.

The raids also bought him some leeway with Vatican hierarchy. They allowed him to operate unhindered even though his work technically violated the Church’s neutrality. Pius XII temporarily turned a blind eye.

As Allied forces clawed their way north invaded Italy and began the long march up the “boot” of the country, Kappler became increasingly involved in hunting down suspected Allied agents and Allied POWs that had escaped from their camps after the surrender of the Italian Army.

The Gestapo Chief’s informants and contacts in the neo-Fascist Italian police advised him of a certain Irish priest who was finding ways to facilitate the escape from Rome of Allied POWs, Jews and others.

All of Kappler’s intelligence pointed to a Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty as the head of a shadowy network of priests, nuns and lay people who hid refugees and aided in their escape. He ordered a white line be painted around the international border of neutral Vatican and Italy.

He disseminated the information that if O’Flaherty crossed that line, he would be killed. Anyone aiding the Monsignor would be arrested. Unable to cross the line himself, lest he violate Vatican neutrality, he formulated plans of assassination and/or kidnapping O’Flaherty. The brutal Ludwig Koch, head of the Fascist Italian police in Rome, promised torture of O’Flaherty would precede any execution.

Kappler was notified that O’Flaherty was visiting the home of Prince Doria Pamphili, an anti-Fascist nobleman who had been a source of funds for The Escape Line. The Prince’s home was outside Kappler’s white line. The Gestapo Chief immediately assembled a raiding party and surrounded the residence. The Prince was alerted, handed over a 300000 lire contribution and told O’Flaherty that the house was surrounded by Germans. O’Flaherty gratefully accepted the Prince’s donation and ran down the stairs to the coal cellar. A coal truck was unloading the Prince’s winter fuel.

He pulled off his robes, stuck them a nearby coal sack, smeared his face with coal dust, slung the coal sack over his shoulder and in his shirt and trousers, climbed through the trap door to the courtyard. He calmly walked across the courtyard pass the cordon of SS men and around the corner of a nearby building. Dropping the bag, he retrieved his robes, put them on and made his way back to his Vatican apartment.

Kappler was furious he had missed his man.

O’Flaherty said a prayer and reconsidered his safety. He decided to positioned himself on the steps of St. Peter’s in his ceremonial robes and read his breviary. He was in full view of a Gestapo surveillance squad across the white line in front of the church. Nuns and priests who worked for the Escape Line would meet him there to receive and deliver messages and cash. Facing the Monsignor with their back to the surveillance team, the exchange was undetectable.

Kappler tried a new tactic. One of his prisoners was a delivery man who had been caught bringing in supplies to a market in Rome and ferrying Escape Line money back to country families who were hiding escaped prisoners. Kappler offered him a deal: help trap the Monsignor or be shot. The man agreed to help.

He made contact with O’Flaherty and told him he had some information about an escapee. The priest asked the man to meet him at his usual spot in the morning. May didn’t think the man’s story rang true. He positioned himself with three Swiss guards so he could watch the meeting.

A dark Gestapo car pulled up to the white line with its engine running. The man approached the Monsignor, lost his nerve and ran down an alley. May caught the man and offered sanctuary. It wasn’t a hard sell.

Kappler slammed his fist on his desk. He growled, “Ach, du Hurensohn (the son of a bitch)!”

On March 23, 1944, the 25th anniversary of the founding of Mussolini’s Fascist movement, a group of anti-fascist resisters, the Patriotic Action Group, Gruppi d’Azione Patriotica, detonated a 40 lb. dynamite bomb near a group of SS policemen, killing 33.

When the news reached Hitler he roared that the entire neighborhood where the attack took place should be blown up, including everyone who lived there. If any German police or soldiers were killed they should shoot between 30 and 50 Italians.

That order was ignored but Kappler did recommend a reprisal action. Field Marshall Albert Kesselring, Commander-in-Chief South agreed and authorized retaliation. Ten Italian civilians would be executed for each policeman killed.

The following day, March 24, 1944, two subordinates of Kappler, SS Hauptstrumfuhrer (Captain) Erich Priebke and Karl Haas, rounded up 335 Italian males. Ranging in age from 15 to 75, many were political prisoners; some were Jews and a few innocent people who happened to be in the vicinity of the attack.

Not a single one had anything to do with the attack on the policemen.

They were marched to a series of man-made caves on the outskirts of Rome. The Ardeatine Caves were the remnants of ancient Christian catacombs. The perfect place to carry out the reprisals in secrecy and to conceal the bodies. The victim’s hands were tied behind their back; they were ordered to kneel and were shot at the base of the skull at close range. Explosives were detonated at the mouth of the cave, entombing the dead.

As the news of the executions spread, the escape organization found more and more people who would help even though they knew capture meant immediate death.

An additional 2000 police and troops were brought into Rome to control the situation. Movement within the city became difficult.

Kappler initiated random investigations throughout the city. The Germans would suddenly cordon off a street and examine the identity cards of everyone caught in the net. If an escapee was caught, he/she would be unceremoniously hauled off to prison. If an Italian of military age were caught, they would be sent to work in labor camps.

Rome fell to the Allies on June 4, 1944. Gestapo Chief Herbert Kappler tried to seek refuge in the Vatican, but he was arrested by the British and turned over to the new Italian government in 1947. He was tried by an Italian military tribunal on charges of war crimes arising out of the massacre in the Ardeatine Caves. He was found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment for life.

During his imprisonment he and his first wife had divorced. He remarried a nurse, Anneliese Wenger Walther, a daughter of a German officer, with whom he had carried on a frequent correspondence. They had a prison wedding in 1972. Throughout his time incarcerated, he had only one visitor other than his wife: his one-time opponent, Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty. They discussed literature and religion. Kappler eventually converted to Catholicism.

In 1975, at the age of 68, Kappler was diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer. He was moved to a military hospital. Because of his deteriorating and his wife’s nursing skills, Anneliese Kappler had unlimited access to her husband.

There are several versions of how he managed to escape. One is that on a visit, she bundled Kappler into a large suitcase (he weighed only about 100 pounds at the time) and with the help of some of the unknowing staff, lugged him out, deposited him in her rented Fiat and escaped to freedom to West Germany.

Another is that on a visit, she brought some clothes and had Herbert dress in a suit. She left the room, went down to the ground floor and re-parked their rental car close to the building entrance. There was no guard on duty. She returned to the upper floor, made up his bed to appear as if someone was sleeping in it, placed a note on the door, “do not disturb before 10am” and holding him tightly, they made their way down the stairs to the car and freedom.

A diplomatic firestorm ensued. The Italians demanded that Kappler be returned. The West German authorities responded that Kappler, as a POW, was entitled to escape and refused.

Six months later, the SS Oberstrumbannfuhrer and Gestapo Chief died at home on February 9, 1978.

Monsignor O’Flaherty was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm. Subsequently, the President of Italy awarded him a silver medal.

In 1953, Pius XII made the monsignor a Domestic Prelate. It was an honor conferred on priests who have undertaken outstanding work. Six years later, he was appointed Head Notary of The Holy Office. All subsequent documents and decrees published by this office carried his name.

On October 30, 1963, Hugh O’Flaherty went to his final reward. His funeral Mass was celebrated.

He was awarded The Commander of The British Empire (CBE) by Great Britain. The CBE is a third level award made to civilians. The U. S. awarded the Monsignor a Medal of Freedom with a Silver Palm, a second level civilian award.

30-10-2013:The Hugh O’Flaherty statue on Mission Road, Killarney on Wednesday.

Picture by Don MacMonagle

There is a small monument to him in the town of Killarney and a small grove of trees in the Killarney National Park dedicated to him. Despite this, he’s practically an unknown in his native country.

Two medium level awards and a grove of trees named after a man that saved an estimated 6500 lives.