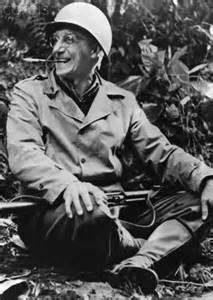

Lieutenant General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell came by his moniker honestly. The U.S. commander of the China- Burma-India Theatre, which included American, Chinese, some British and assorted native fighters in Southeast Asia was tough, brilliant, abrasive, opinionated and difficult. He suffered inefficiency and stuffiness badly.

From early in his career, his short temper and colorful language made him stand out. A strict religious upbringing instilled in him an early intolerance for anything he considered incompetent and a distain for structure despite four years of discipline at West Point. He showed an early aptitude for languages and was first in his class in French.

After a stint as a Combat Intelligence Officer in WWI, he was posted to China. He scorned the life of leisure and parties that many expatriates there enjoyed. He made the unusual decision to study Chinese and spent six years in studying and mastering that difficult language and traveling the countryside. He saw first-hand the suffering of the Chinese people and witnessed the Rape of Nanking when the Japanese massacred 40000 civilians. His diligent information gathering made him one of America’s top experts on China.

Despite his blunt personality, his brilliance provided a steady rise in the ranks. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he was bucked to Lieutenant General and appointed Military Attaché in China by Chief of Staff George C. Marshall who acknowledged he was giving Stilwell “one of the most difficult assignments” in the war. He took charge of all American and Chinese forces in Burma.

Several well-known combat units came under his purview: Colonel Claire Chennault’s “Flying Tigers;” General Frank Merrill’s “Merrill’s Marauders;” “The 1st Commando Group;” AAF’s “10th Air Force” flying C-47s and DC-3s transports over the mountains (“The Hump”) bringing supplies to Chiang’s army; and British General Orde Wingate’s “Chindit Raiders.”

He found the average Chinese soldier fought well if properly led, but they were poorly equipped. Supplies weren’t organized. Their commanders lacked boldness and courage. He found corruption and politics at every turn in the upper ranks of the Kuomintang (Nationalist) Army. The main problem was its leader, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

Little more than a warlord, Chiang knew that as the principle U.S. ally in China, the U.S. needed him to fight the Japanese to take pressure off of Allied (U.S. and British) forces. He would renege on his promises, countermand Stillwell’s orders and threaten to withdraw form the campaign if American didn’t send more supplies.

Little more than a warlord, Chiang knew that as the principle U.S. ally in China, the U.S. needed him to fight the Japanese to take pressure off of Allied (U.S. and British) forces. He would renege on his promises, countermand Stillwell’s orders and threaten to withdraw form the campaign if American didn’t send more supplies.

He constantly demanded more. More of everything, rations, guns, bullets, equipment and sometimes money.

He was reluctant to commit his army to the war with Japan, believing he had to preserve it for an eventual conflict with Mao Tse-Tung’s Communist army.

Stilwell was placed in a no-win position while trying to defeat a determined enemy. He was forced to juggle conflicting responsibilities: A U.S. general responsible to the U.S. Joint Chiefs with orders to improve the training of the Kuomintang Army in the fight with Japan; a deputy to the Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, the egotistical Lord Louis Mountbatten Chief of Staff; and, most importantly, “minder” of Chiang.

His chore was made more difficult by his no-nonsense personality. He generally disliked the British and loathed Chiang, regarding him as a tinhorn warlord incapable of military professionalism, nicknaming him “Peanut.” He put enormous effort into negotiating and managing Chiang. It was an experience that embittered both men.

Still, grinding his teeth, Stilwell struggled to bring Chiang around, despite his duplicity and foot-dragging. The bitterness between them didn’t go unnoticed and Stilwell was offered another command to defuse the situation, but he stuck with the job.

In his hurry to out-do the despised Brits, he made several impulsive tactical moves with Wingate’s Chindits and Merrill’s Marauders. He flung them into unnecessary frontal assaults on targets, which caused enormous losses.

His bull-headed determination was wearing thin on his allies. Problems with Chiang continued. Impulsively, he sent a blunt message to FDR regarding the situation. The enormously effective Chinese political lobby in Washington, led by Madame Chiang, demanded Vinegar Joe’s removal. Needing the Chinese military effort to keep pressure on the Japanese, FDR pulled the plug.

Recalled to Washington, he was showered with honors, but the experience left him a bitter man. He had been unceremoniously sacked and told not to discuss the “China Problem” with anyone, especially the media.

He was transferred to Okinawa. With the death of the land commander there, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, he assumed command of the ground forces in that final land battle of the war.

He served until war’s end and was present at Japan’s surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri in September of 1945.

He died the next year from stomach cancer.

“Vinegar” Joe was a brilliant and difficult commander caught in an untenable position. It was a shame that politics did him in. One wonders what he could have accomplished had circumstances been different.