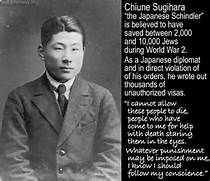

Chino Sugihara

Better known as “Sempo”, Sugihara was a Japanese diplomat who came into prominence in WWII. He was responsible for saving the lives of thousands of European Jews by providing them with the necessary papers that allowed them to emigrate to Japan.

Born into an upper middle-class family, Sempo was encouraged by his father to become a physician. But he had other ideas. He purposely flunked the medical school entrance exam and decided a career in diplomacy was a better fit for him. He studied English in Tokyo, then applied for the foreign ministry in 1919 and was accepted.

His first posting was in Harbin, China where he was involved in negotiations with the USSR, the Chinese and Japanese in a dispute over the Northern Manchurian Railroad.

While there, he learned German and Russian and became an expert on Russian affairs. His star was rising, but his concern over the treatment the Chinese were enduring under Japanese rule got him marked as a “disobedient servant of the Empire.”

But his talent and skill as a diplomat was in great demand by Japan. He was posted to Lithuania and given the title of vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in 1939.

His primary responsibility was to keep an eye on Soviet-German relations and report their activities to his superiors in Berlin and Tokyo. This brought him in touch with Polish intelligence. When Hitler decided to start WWII in September 1939 by invading Poland, Jews, knowing of his anti-Semitism, fled to Lithuania. The following year, Stalin, no friend of the Jews, invaded the Baltic States, including Lithuania.

Local Jews and those fleeing German and Soviet armies applied for exit visas. But no sovereign country, except The Netherlands, would accept anyone without a valid visa. The Dutch approved access to its colonies in the Caribbean and Suriname in South America, but limited the number of people allowed in.

Thousands of people queued at foreign consulates, desperately seeking permits.

Many people tried to get a visa at the Japanese Consulate, but the strict immigration criteria meant that very few were successful.

Sugihara requested instructions from his Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but they instructed him to issue visas only as a transit option to a third country.

The vice-consul decided to follow his own counsel. He could see that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed in August 1939, (a non-aggression pact between the Soviets and Germany), was a fig leaf designed to buy time for those countries to beef up their military forces. It was just a matter of time before Lithuania would be caught in the middle of two massive armies in a life-or-death struggle.

During the summer of 1940, Sugihara ignored Ministry orders and began to issue visas to as many people as he could. He secretly met with Soviet officials and negotiated with them so that people could travel on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The Soviets saw a sellers market and quintupled the price of a ticket.

Sempo, as the Jews popularly knew him, became a beacon of hope. He wrote almost around the clock, issuing a month’s worth of visas in a single day.

When war broke out, the consulate was ordered closed and he was ordered to evacuate, but he continued to issue visas even as he was taken to the railway station. When the train began to pull out, he stamped and signed blank sheets of paper and handed them out so they could be forged into legitimate exit visas.

As the train picked up speed and began to leave the station, he threw more documents out of the window, shouting, “Forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

A man in the crowd shouted back, “Sugihara! We will never forget you!”

As the train left the station, Sempo sat down, put his head into his hands and wondered about his fate. He hadn’t had much time for that. His superiors would surely punish him severely.

But sometimes Lady Luck smiles. In the confusion of the hasty closure of the consulate, Sugihara avoided detection as many of the higher ranking officials attended to securing their own survival. They never learned how many exit visas Sempo issued.

As it turns out, a lot. Research estimates about 6000. Some of them were group permits that enable whole families to get away. Some estimates suggest a total of 10000 people. Sadly, not all managed to escape. Hitler tore up the non-aggression pact he had with Stalin and launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Many Jews were trapped and killed.

Sugihara spent the rest of the war serving in consulates in Prague and Bucharest before he was captured by Soviet troops in 1944. After spending two years as a POW, he and his family returned to Japan in 1946.

Forty years later, his heroic action was recognized by Israel and he was given the title Righteous Among the Nations, reserved for Jews who resisted the Holocaust and Gentiles who helped them in time of need.

When asked why did he help all those people, Sempo quietly replied, “I do it because I have pity on the people. They want to get out, so I let them have the visas.”

His heroism went largely ignored during his lifetime. After his death, he was awarded some minor honors and a few streets were named after him, but he remains an Unsung Hero.