Hedy Lamar

On November 9th, 1913, the Kiesler family welcomed the birth of Hedwig Eva Marie Kiesler into their family. The Kieslers were a prosperous Viennese Jewish couple. Her mother had converted to Catholicism. Her father was secular. Their daughter, as she grew older, always kept her Jewish heritage secret.

Her favorite parent, father Emil, was a successful banker with a mind of a mechanical engineer and an enthusiasm for technology. Little “Hedi” cherished the walks they would take in the nearby park of the Wienerwald — the Vienna Woods. He would explain to her how various mechanisms worked. Emil’s interest in inventions kindled in her a natural inquisitiveness in inventions that would remain with her all of her life.

An only child, she entertained herself with her dolls and dreamed of becoming a movie star. She acted out little fairy tales for her parents. “I acted all the time. I copied my mother. I copied her mannerisms. I copied people in the streets. I copied the servants. I wrote people down on me.”

When she was 15, Hedi met theatre director and impresario Max Reinhardt. He was impressed by her and encouraged her to pursue her dream of becoming a famous actress.

She skipped school, scoured the theatres and movie studios all over Vienna. She found an opening for a script girl at a large motion picture studio. Despite not knowing anything about what script girls do, she talked the director into the job. A day later a small part became available for a girl in the picture currently in production. She auditioned for it and secured the role. There was no going back.

She had to tell her parents her decision. She intended to drop out of school and become a professional actress. She told several versions of the story later in life:

“Well, it wasn’t too bad. They were bewildered but not surprised. They were never surprised at anything I did…my dear father laughed and said, ‘You’ve been an actress ever since you were a baby!’…. they were willing to give me this great wish for my heart.”

Another version was that she persuaded the director to give her the part, but her parents “were much more difficult to persuade than [the director], because it meant my dropping school. But at last they agreed. My father… reasoned that I would soon enough quit of my own accord and go back to school.”

Bigger and better roles followed. Reinhardt cast her in a number of plays that gave her exposure, developed her expertise and built her confidence.

It was at this time, Reinhardt claims, to have given Hedi her life long first name, Hedy. He told reporters “Hedy Kiesler is the most beautiful girl in the world.” That description was to follow Hedy for the rest of her life.

Berlin was the center of filmmaking at that time. She traveled there, looking for work. “As soon as I was acting in a studio, I wanted to be starring in a studio.”

She starred in a number of films. A leading role became available. She was offered the lead in a Czech film, “Ekstase” (Ecstasy). She jumped at the chance and moved to Prague. It was a career changer.

Ekstase was a love story about a young woman, married to an older fussbudgety man. On a trip to a wooded area, she stops to swim au natural in a pond. A virile young man happens by, sees her and falls in love with her. Back home, she struggles with strong feelings for him. They agree to meet in his cabin for a night of love. During the lovemaking, without nudity, Hedy delivers an erotic close-up of a woman having an orgasm. She was the first woman to appear naked in film. It created a sensation and a new star. She was 18 years old.

She returned to the stage in a musical comedy in Vienna. In the audience was the industrialist Friedrich “Fritz” Mandl. Thirty-three years old, he was a stocky, short, assertive man and the third richest man in Austria. He had a reputation as a womanizer and social climber. Called “The Cartridge King,” he managed his family business, Hirtenberger Patronen-Fabrick, an ammunition and arms factory.

He was smitten and began an aggressive courting campaign to win fair Hedy. Great baskets of flowers with personal notes were delivered to her, all of which were returned. He called her every day, imploring her for a dinner date. Her indifference seemed to beguile him. He doubled his efforts. Slowly the ice began to thaw.

“He was so powerful, so influential, so rich, that he had been able to arrange everything in his life just as he wished it….”

Hedy found there was much to be attracted to in Mandl. “I began to feel attracted to the brain of this man, by his tremendous power, by his charm…I love strength. I love it.”

Shortly thereafter they were engaged. “I was in love. I was happy….I was proud of him…..he had the most amazing brain. There was nothing he did not know…”

They were married on August 10th, 1933.

Ensconced in a luxurious ten-room apartment, with servants attending to her every need, Hedy lived in opulence and extravagance. The early years of the marriage were happy ones for her. “I felt like Cinderella.”

Initially indulgent and attentive, Mandl gradually came to dominate everything in her life and eventually forbade her to pursue her acting career. She realized she had become a “trophy wife.” She was just another one of his many possessions. The independent Hedy rebelled. Frequent and violent arguments ensued. She was locked in a “prison of gold.” The question was, how could she get out?

Since the 1920s, Mandl had begun to cultivate contacts in right-wing Austrian politics. His business acumen told him that the winds of National Socialism were blowing and he perceived windstorms were on the horizon.

He was convinced that this would be good for business and advance his social standing. With an heir to the defunct Austro-Hungarian throne, he formed a paramilitary movement and supplied them with arms. Ostensibly to root out clandestine Socialist weapon caches, his militia fought in a series of bloody fights. After these clashes, Nazi partisans, with promises of law and order, grew in number and power.

Mandl began to woo industrialists who had Nazi sympathies. There were regular lavish dinner parties at the Mandl mansion. “We entertained….diplomats and men of high political position, makers and breakers of dynasties, financiers who manipulate the stock exchanges of the world,” Hedy said.

There were many inventors, industrialists and engineers who visited the Mandl mansion during those years. They talked openly about developing German military technology. Mandl’s beautiful wife smiled, listened and paid close attention, particularly when the discussion turned to torpedoes.

Impressed by her beauty and pleased by her deferential questions, they were forthcoming with a good deal of technical information. They didn’t suspect this glamorous house frau was intently focused on their remarks. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she famously said later in life. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” The knowledge she gleaned by looking “stupid” would be her capital as she planned her escape from the “prison of gold.”

In the 1920s, a young American composer was writing avant-garde music in Paris. He had not been able to find an audience for his music in the U.S., but Europe was responsive. He was trying to create a distinctive American music. Strangely, he did not find inspiration in any forms or composers of American music. He was drawn to the Russian masters. Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg were his favorites. As he tried to carve out an audience for his compositions, he made a living as a concert pianist performing classical music.

Child prodigy, high school dropout, concert pianist and avant-garde composer, George Antheil’s compositions drew mostly mixed reviews. They were considered “brilliant” by Aaron Copeland. Another reviewer said they sounded like “a calliope in a circus parade.”

One of the most popular home entertainments at the time was the player piano. They had grown in such popularity they began to outnumber standard pianos. It wasn’t necessary to take piano lessons or years of practice to be able to play. They had internal mechanical workings and the instrument could be played by hand or mechanically.

Music on player pianos was recorded on rolls of tough paper. Technicians cut slots and holes in the paper to correspond to the notations on sheet music. The roll was loaded onto spools in the piano. Pumping pedals near the bottom of the piano scrolled the paper roll over a row of vacuum ducts, one for each piano key. The spooling paper covered the ducts until a slot or hole allowed air to be sucked into the duct. A tube connected the duct to a series of valve chests. The air from the tube flowing into the valve chests activated a sequence of valves and bladders that drove a pushrod that activated the piano key.

Antheil was fascinated by its musical possibilities. He composed several pieces of music for it. When he performed them in Paris, his detractors and admirers were about evenly divided.

In 1926, he premiered his Ballet Mecanique with an orchestra of 85 musicians. Eight grand pianos and eight player pianos, operated by cables, were attached to a master keyboard onstage. The score also required electric bells, saws, hammers and two airplane propellers.

Shortly into the concert, bedlam ensued. Booing, cat-calls and whistling (the highest form of contempt in France) was mixed with shouts of “bravo” and cheering. Antheil grimly continued to play. When it was over, he got an ovation that exceeded the cat-calls.

The dark shadow of National Socialism was drawing across Europe. The post-war liberal, conventions-be-damned atmosphere personified in the popular song of the day, “I Don’t Care, I Don’t Care,” began to disappear. The avant-garde was becoming “decadent.” The chaos of the great European Depression made people long for structure and order. The Nazis provided that and pulled the country out of its depression. The cost? Adherence to “The New Order.”

Antheil, now married, knew it was time for him to return to America. He had heard about employment in Hollywood as a composer for film music. He also heard the climate would help his on-going battles with asthma.

He had become an amateur student of endocrinology over the years. He was fascinated with the possibility of predicting human behavior based on which hormones dominated a person’s physiology. Over time, he devoured every book he could find on the subject.

His knowledge of the burgeoning science of endocrinology brought him to the attention of Arnold Gingrich, the editor of a new magazine, Esquire. Antheil, needing to have another source of income, began submitting article after article.

Hedy told several stories in later years about how she escaped her suffocating life with Fritz:

The most elaborate involved picking out a maid that most resembled her physically, befriended her and drugged her with sleeping pills, dressed in her uniform and slipped out of the house, caught a train to Paris, filed for divorce and moved to London.

The one historians seem to feel is closest to the truth is:

She attended Fritz’s company Christmas party at his factory in Hirtenberg, Austria. Afterward, she spent the winter in St. Moritz. Her husband was away on business. She returned to Vienna determined to revive her acting career. Mandl returned and was staunchly opposed. They fought ferociously. Fritz stormed off to one of his hunting lodges.

Hedy knew this was her chance. She stuffed several suitcases and trunks with all the jewelry and furs she could. She left Vienna that night, veiled and incognito and went to London.

In London at a dinner party, she met Louis B. Mayer, head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. He was on a “talent safari” in Europe for writers and actors.

Again, her story varies: Mayer shows tepid interest. His safari complete, he and his wife, Margaret, set sail for America. Hedy sells some jewelry and buys a ticket on the same ship. During the voyage, begins to “work” Mayer. After many meetings and discussions, he agrees to give her a contract. She must learn English and agree to change her name.

The name change story varies. The one that seems to have the most credence is that Mayer didn’t like the name Kiesler (too German) nor Mandl (possible lawsuits). One of Hollywood’s most famous silent screen actresses, Barbara La Marr had died several years earlier. MGM owned the rights to the name. Mayer said, “We’re going to replace death with life.”

When the ship docked in New York, it was Hedy Lamarr that walked down the gangplank. A new life had begun.

She spent her first few months in Hollywood perfecting her English, getting in top physical shape and attending parties.

Finally, a starring role became available. She appeared opposite Charles Boyer in the film Algiers. It was about a jewel thief, Pepe Le Moko, (Boyer) hiding out in the Casbah, the Arab quarter of the North African city of Algiers. He meets a beautiful French tourist, Gaby (Lamarr) and falls in love with her. Their romance draws him out of hiding to be with his new love. Enraged, his jealous mistress betrays him.

The movie was a huge hit and propelled Hedy to full-fledged stardom. (No, the famous Boyer line, “Come wiz me to ze Casbah” was not uttered in the film, but was in the movie’s trailer).

The film’s success gave Hedy more time on her hands. She occupied much of that inventing. She had an area of her house given over to inventing. While others spent their spare time with card games, reading or playing the piano, Hedy worked on a bouillon-like cube which, when mixed with water, made a Coca-Cola like drink. Or a tissue-box attachment that was utilized to dispose of used tissues. The work challenged and stimulated her in a way card games couldn’t. Her other favorite pastime was hosting small dinner parties with intellectually interesting people.

At one of these soirées, Hedy met Gilbert Adrian, a clothing designer who styled himself as simply “Adrian.” His designs were in demand at several of the major studios and popular among American women.

The Antheils were good friends with Adrian. He invited Antheil to join him at one of Hedy’s dinner parties. Antheil and Hedy were both intelligent, articulate people, both spoke flawless German and both enthusiastically anti-Nazi.

Several stories abound regarding the invitation. The one that is supposedly closest to the truth is that Hedy had heard about Antheil’s endocrinology knowledge. She was concerned that her breasts were too small and wanted to know “……can they be made bigger?” Antheil assured her they could be.

As the story goes, after the party, Hedy wrote her phone number on his windshield with her lipstick as she was leaving. The next day he called her and she invited him to dinner over which they discussed “various glandular extracts” that would enhance her breasts. Later, the conversation drifted to the war, which by 1940, was in full swing, even though the U.S. hadn’t officially entered yet.

Hedy evidently thought her knowledge gleaned from her years rubbing elbows with Mandl’s weapons systems associates would be useful to the government. She naively suggested she quit MGM and make herself available to the National Inventors Council. The NIC was a newly established government clearing house for inventions of possible military and/or national defense uses. “They could just have me around and ask me questions,” she explained. The NIC politely declined.

One of the guests that had attended Mandl’s dinner parties was Hellmuth Walter. Hedy initially met him at the annual company Christmas party at the Hirtenberger factory. He was a mechanical engineer and an expert at torpedo development. He had developed a remote controlled, wire guided torpedo powered by hydrogen peroxide that made no tell-tale wake. At dinner, charmed by the beautiful Frau Kiesler Mandl, he told her about its development and its underlying technology. He had no idea this beautiful young woman who nodded and smiled sweetly was intensely absorbing his ideas. The scientific application of torpedoes had captured her interest.

U.S. Navy torpedoes during the early years of the war were notoriously inefficient. As the war progressed, the Navy learned they had a multiplicity of problems with the weapon. They were running too deep, exploding too soon, or did not explode at all. The firing mechanisms were unreliable. In the early years of the war, 60% were duds.

Naval historian Theodore Roscoe said, “The only reliable feature of the torpedo was its unreliability.” One major flaw was that radio-controlled torpedoes operated on a single frequency signal could easily be jammed. Broadcasting interference at the frequency of the control signal would cause the torpedo to go off course.

Antheil and Hedy developed the idea of a wireless, radio-controlled torpedo-guidance system. It would incorporate a transmitter synchronized with a receiver. The ship firing the torpedo (transmitter) would send command signals to the torpedo (receiver). By changing their tuning simultaneously, quickly hopping randomly from frequency to frequency, the radio signal passing between them could not be jammed.

Antheil’s main contribution was to introduce the use of player piano rolls. Consisting of 88 keys and punched with the identical pattern of random holes, the transmitter and the receiver could be controlled using 88 different, shifting, short-burst frequencies. Hedy called the idea Frequenzsprungverfahren, literally, “frequency hopping process” or simply, “frequency-hopping.”

In late 1940, they made a package of blueprints, directions, and explanations and sent them to the NIC. The Council immediately showed interest in the project and asked for further information which was duly sent. The following June, they filed their patent application. Patent # 2292387, issued on August 11th, 1942, covered a broader, more fundamental system they called the “Secret Communication System.”

A patent lawyer suggested Hedy and Antheil make future modifications on their patent which would extend its rights. They didn’t take his advice. They never followed through on efforts to extend the “life” of their patent.

Hedy and Antheil offered their invention to the U.S. Navy. Under the circumstances, they had no interest in developing a complicated guidance mechanism. They would be happy to get their old-fashioned unguided torpedoes to hit their targets and explode. Saying “that it was too bulky to be incorporated in the average torpedo,” they decided to pass.

They suggested Hedy could help the war effort more effectively by promoting the sale of war bonds. She did just that, raising nearly $25 million dollars. She sold kisses for $50000. a smack. But she continued to be interested in inventions, particularly those involving torpedoes.

The frequency-hopping concept languished until 1962. The U.S. Navy, during the Cuban missile crisis, implemented it on their ships during the blockade of the island. Why the Navy acquired the patent to a technology it had formerly rejected and kept that technology secret for over 40 years is still a mystery.

Lamarr’s and Antheil’s patent is the foundational patent for modern spread-spectrum communications. Twelve hundred patents refer to it. Bluetooth, COFDM (Coded Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing — used in Wi-Fi connections) employ aspects of that technology.

In 1998, a Canadian wireless technology developer, Wi-LAN Inc., acquired a 49% interest in Hedy’s patent for an undisclosed amount of stock. Otherwise, Hedy and Antheil, who had died in 1959, received no compensation for their groundbreaking invention.

Today spread spectrum devices using micro chips make cell phones, pagers and communication on the internet possible. The technology is used in the U.S. government’s multi-billion dollar Milstar system. Milstar is a network of communications satellites in orbit providing jam resistant communications to the Armed Forces.

Hedy’s later years weren’t kind to her. Good film roles gradually evaporated and the flow of scripts dried up. She found occasional work in television, but mostly as a celebrity guest. She had earned a great deal of money, an estimated $50 million ($372 million today), but six divorces under California’s community property laws, attorney’s fees from a never-ending parade of lawsuits she initiated and lavish lifestyle consumed much of it.

There were charges of petty shoplifting from which she was acquitted.

By the 1980s, she had moved to Florida. Now in her 70s, her health was in decline and her eyesight was failing. She was on a tight budget and becoming reclusive.

On January 19, 2000 Hedy put on her makeup, coiffed her hair, applied perfume, dressed tastefully and lay down on her bed. She passed away sometime during the night. She was 86. At her request, her ashes were scattered in the Wienerwald in Vienna where she had walked with her father and learned about everything from printing presses to streetcars.

“My life was full of colors, full of life and above and below and over and under. But I don’t regret anything…”

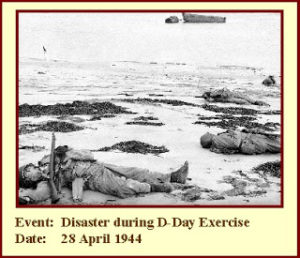

Assault conditions were made as realistic as possible to accustom the troops to true combat conditions that they would face on D-Day, including live firing from naval guns and on-board artillery. Individual soldiers also had live ammunition in their weapons.

Assault conditions were made as realistic as possible to accustom the troops to true combat conditions that they would face on D-Day, including live firing from naval guns and on-board artillery. Individual soldiers also had live ammunition in their weapons.