1942 started out badly for the United States. It was licking its wounds from the Pearl Harbor assault the previous December. The U.S. Navy was working around the clock to repair the damage inflicted on it by Japan. Morale in the country was below low.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew something had to be done. And done quickly. In a meeting with The Joint Chiefs of Staff in late December 1941 he insisted that Japan be bombed as soon as possible. Only retaliation would boost public morale.

The Japanese High Command had told the Japanese people that they were invulnerable to attack from the U.S. An attack on their homeland would create doubt about the reliability of their leadership.

But how?

The U. S. didn’t have a bomber that could reach the Japanese homeland from Hawaii, its most forward base in the Pacific.

Navy Captain Francis Low, assistant Chief of Staff for anti-submarine warfare, had an idea: What if a flight of twin-engine medium bombers could be brought close enough to Japan to successfully inflict damage on that country? He ran the idea by Chief of Naval Operations, the stern, aloof Admiral Ernest J. King.

Instead of chewing Low out for taking his time with such a cockamamie idea, King liked the sheer audacity of striking back at an enemy that had nearly destroyed “his” Navy.

The raid was planned and led by aviation pioneer, flight instructor and test pilot, USAAF Lieutenant Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle.

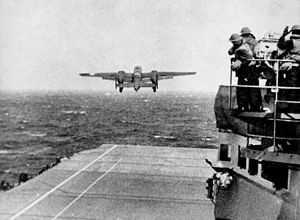

The bombers would have a cruising range of 2400 nautical miles with a 2000 lb. bomb load. Mitchell B-25B bombers would be modified to hold twice their normal fuel reserves, which would double their 1300 nautical mile range. The bombers would have to make the trip without a full compliment of guns and without fighter escort.

Furthermore, it would have to be a one-way trip. The launching carrier couldn’t land the bombers.

A runway was painted with an outline of a carrier deck on an auxiliary airstrip at Elgin Field in the panhandle of Florida. The all-volunteer crews practiced takeoffs, trained for low-altitude bombing and over-water navigation. And practiced. And trained. And practiced. And trained. Absolute secrecy surrounded their efforts. Security was as tight as a drum.

On April Fool’s Day, 1942, sixteen modified bombers, their five man crews and support personnel were loaded aboard the USS Hornet. Each plane carried four 500-pound bombs, three of which were HE (high explosive) and one with incendiaries.

The Hornet got under way the next day, escorted by an additional carrier, the USS Enterprise and a flotilla of cruisers and destroyers. Strict radio silence was maintained. It was pedal-to-the-metal as the task force dashed across the Pacific at 20 knots.

Initially, things went well and according to plan. Then, on the 18th, while still about 650 nautical miles from the Japanese mainland, they were spotted by an enemy patrol boat. The boat was sunk by Navy gunfire, but not before a warning had been radioed to Japan.

Doolittle and the Hornet’s captain, Captain Marc “Pete” Mitscher decided to launch immediately, 170 miles further from the targets than planned. All planes were stripped of any non-essential equipment and guns.

All aircraft were launched successfully and broke formation to fly singly at wave-top level to avoid detection by Japanese radar.

The aircraft arrived over Japan at noon local time, climbed to 1500 feet and bombed 10 military and industrial targets.

The Japanese were caught completely by surprise. People on the ground thought the planes were theirs and waved and shouted encouragement to the airmen.

After dropping their bombs, the flight crossed over Japan and crossed the E. China Sea toward China. The plan involved landing on the China coast where they would be refueled by Chinese partisans at a place called Zhuzhou. They would then fly to the interior of China to Kuomintang (Nationalist capital) and American ally, Chiang Kai-shek, who would receive the flyers, take the planes as part of U.S. lend-lease and see that the crewmen returned to the U.S.

But night was approaching, the weather was turning bad and fuel was running low. Luckily, a tailwind made it possible for the planes to reach China but not Zhuzhou.

The pilots realized they had two choices: bail out over eastern China or crash land along the coast. All 15 of the planes reached the coast and some took option #1, others #2. The pilot of the 16th plane, convinced he couldn’t make the coast, veered off and landed in the Soviet Union, where their aircraft was confiscated and the men interred (they languished there for over a year).

Some of the crews, including Doolittle, with the help of Chinese civilians and soldiers managed to eventually return home. Doolittle thought he was going to be court-martialed for losing all of his planes.

Instead, the raid bolstered American morale such that Roosevelt promoted him two ranks, jumping him from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general and awarded him The Medal of Honor.

All 80 raiders received the DSC (Distinguished Flying Cross). All those killed or wounded received a Purple Heart. The Chinese government decorated all Raiders.

Not all made it home. Three were KIA, eight were taken prisoner, of which one died in captivity, the others executed by the Japanese. Twenty-eight stayed and fought on in the China-Burma-India theatre and several died there.

The Japanese were furious about the attack. They scoured the Chinese countryside for the Raiders and killed many Chinese whom they suspected of helping them. Estimates of up to 10000 civilians lost their lives.

The military impact on Japan was little more than a mosquito bite. But American morale soared. The Japanese High Command “lost much face.” They could no longer assure their people they were invulnerable from American attacks.

They hadn’t seen anything…yet.